This early period is enhanced by apt and tender dialogue, like the “practiced quarrel” between Libertie’s mother and her friend. “I nodded politely,” she narrates, “not committing to my guest’s belief but trying to be neighborly, which is what we learned in Sunday school.” The child persists in believing her mother has raised this man from the grave, and prays and writes songs to his dead lover, who she believes lives at the waterfront. Greenidge shines in occupying the young girl’s mind, as when Ben Daisy early on criticizes his new, Northern surroundings. She gazes at her mother when she’s treating her patients, watching for “that look she always got when she left this world and entered the one of her mind.” She knows her mother hasn’t forgotten her only when she offers her child her own mug, “because she knew that I believed that the sweetest drink in the world came from the dregs of a cup she had drunk from.” Though her mother is light enough to pass, Libertie is so dark-skinned that Ben Daisy, the man in the coffin, endearingly calls her “Black Gal.” The young Libertie worships her mother, spending hours working at the clinic and envisioning riding around with her in a horse-drawn carriage inscribed with “Dr. Based on Susan Smith McKinney Steward, the first Black female doctor in New York State, Libertie’s mother founded a clinic in an “all-colored” town called Kings County. War is not far behind them, but Libertie and her mother are both freeborn. The story starts out with a kind of resurrection: A young Libertie’s mother is on the receiving end of an enslaved man’s transport to freedom - inside a coffin. Here as well Greenidge both mines history and transcends time, centering her post-Civil-War New York story around an enduring quest for freedom.

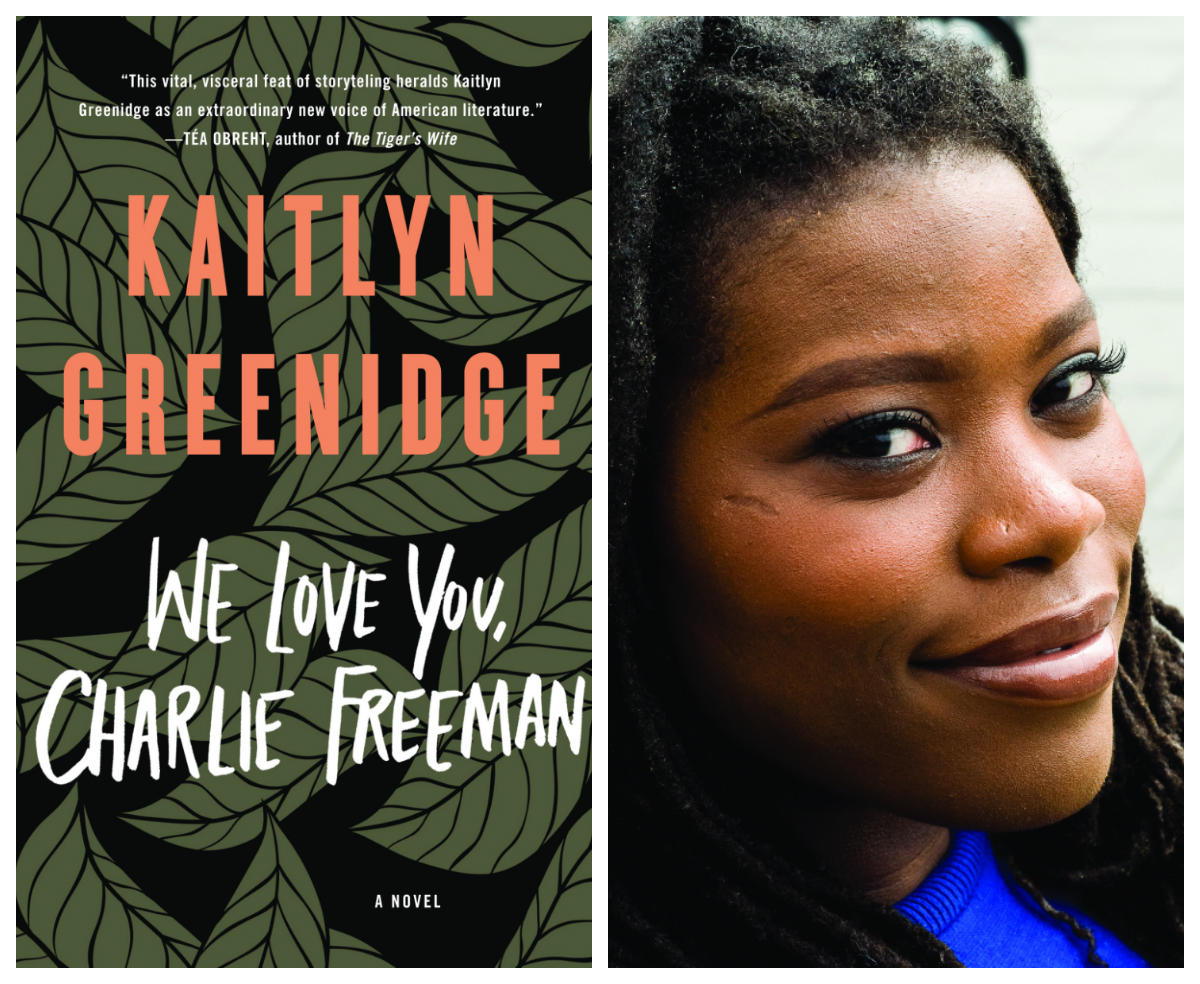

Her 2016 debut, “ We Love You, Charlie Freeman,” paralleled two stories of racial degradation that occurred at a New England research institute six decades apart. Kaitlyn Greenidge’s second novel, “Libertie,” is a feat of monumental thematic imagination.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)